Lung Remodeling Process in IPF Includes Both Traction Bronchiectasis and Honeycombing, Study Suggests

Two clinical hallmarks of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing, may be aspects of one continuous process of lung remodeling rather than distinct entities, as previously thought, according to researchers in Italy. Traction bronchiectasis refers to an irreversible dilation of bronchi, and honeycombing to the diffuse pulmonary fibrosis that characterizes usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).

The study, “From ‘traction bronchiectasis’ to honeycombing in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A spectrum of bronchiolar remodeling also in radiology?“, was published in the journal BMC Pulmonary Medicine.

The histologic (microscopic) features of UIP are the presence of fibroblastic foci and fibrosis in a “patchwork pattern.” Disease progression is characterized by the appearance of airspaces lined by cells with bronchiolar characteristics, ultimately leading to honeycomb changes. This emphasizes the importance of the bronchiolar epithelium (cells lining the bronchi) in the development of UIP.

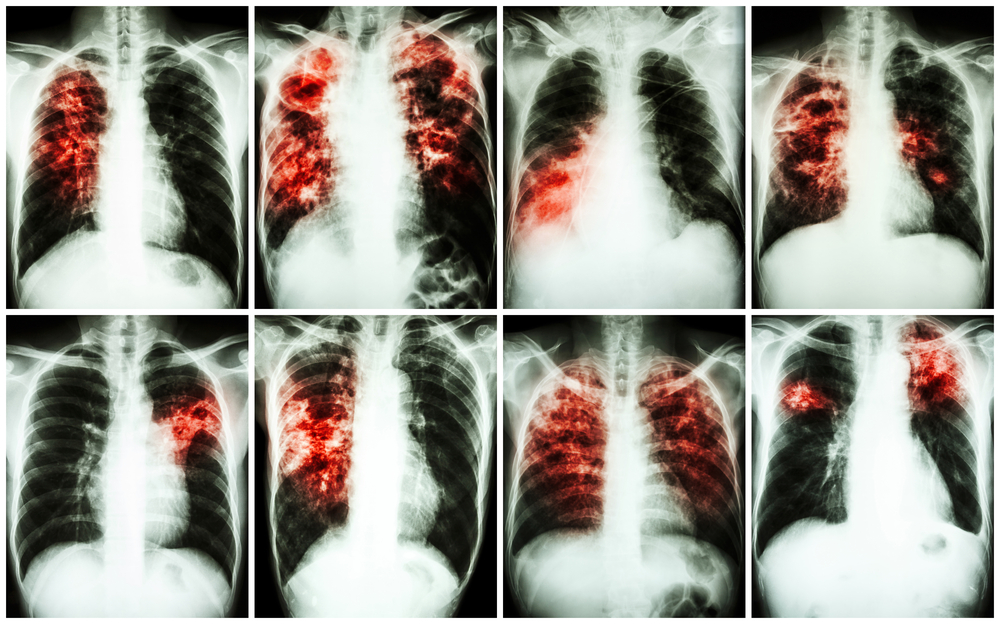

Currently, a “definite” UIP pattern, as observed in IPF patients, is the identification of reticulation, caused by a decrease in the gas to soft tissue ratio, traction bronchiectasis, and honeycombing, as determined by computerized tomography (CT) scans.

It is interesting to note that most of the fibrotic, or scarred, tissue is distant from the traction bronchiectasis area and does not surround the dilated bronchi, contrary to what is found in nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), in which dilated bronchi are completely surrounded by the fibrotic tissue.

However, as the fibrosis progresses, bronchi dilation increases in severity from the lung periphery to its inner regions, eventually overlapping with honeycombing features. Furthermore, CT scan observations suggest that traction bronchiectasis should be interpreted as a result of bronchiolar proliferation rather than just a mechanical consequence of lung scarring, suggesting that traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing may be related events. Consistently, an analysis of the lungs of IPF patients reveal a positive correlation between these two.

“In IPF, remodeling process appears to be a continuum from traction bronchiectasis to honeycombing and conceptual separation of the two processes may be misleading,” the authors, at Ospedale GB Morgagni and their colleagues, wrote.

The researchers believe this hypothesis is in line with the “alveolar stem cell exhaustion” model, which suggests that stem cell exhaustion in the alveoli leads to the aberrant activation of pathways controlling bronchi formation, eventually leading to traction bronchiectasis and later to honeycombing.