Specific Protein Promotes Cell Interaction that Fuels Profibrotic Environment, Study Finds

Written by |

A protein called cadherin-11 (CDH11) ties together macrophages and myofibroblasts in an “eternal hug” in the lungs of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients, promoting a profibrotic environment, a study shows.

Therapies that target CDH11 and break the “hug” between the two cell types may help stop this profibrotic process.

The study, “Cadherin-11–mediated adhesion of macrophages to myofibroblasts establishes a profibrotic niche of active TGF-beta,” was published in the journal Science Signaling.

Myofibroblasts are the cells responsible for repairing tissue after injury. These cells are called to sites by the body’s “first responders,” or macrophages, which are innate immune cells that patrol the tissues in the organism looking for any signs of trouble.

Once macrophages call them into action, myofibroblasts start repairing the tissue by producing a glue (extracellular matrix) made of collagen. Once the tissue is repaired, both myofibroblasts and macrophages are cleared from the injury site.

However, in pulmonary fibrosis, neither macrophages or myofibroblasts dissipate, leading to fibrosis (scar tissue) that persists, ultimately destroying healthy lung tissue.

An extended macrophage recruitment is known to contribute to excessive tissue repair and fibrosis. Based on this, researchers at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Dentistry in Canada decided to further explore the link between macrophages and myofibroblasts in lung fibrosis.

In previous studies, this research team showed that CDH11 levels rise during the transition of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts after treatment with transforming growth factor (TGF) beta-1, a factor produced during repair and a major driver of fibrosis.

Since CDH11 levels increase in myofibroblasts and macrophages during fibrosis and the protein is located at the cell’s surface, researchers hypothesized that CDH11 could actually promote the adhesion, similar to a hug, between macrophages and myofibroblasts.

They first showed that, in tissue from patients diagnosed with IPF, CDH11 levels were higher in fibrotic regions than in normal lung tissue or even tissue from patients with other lung diseases.

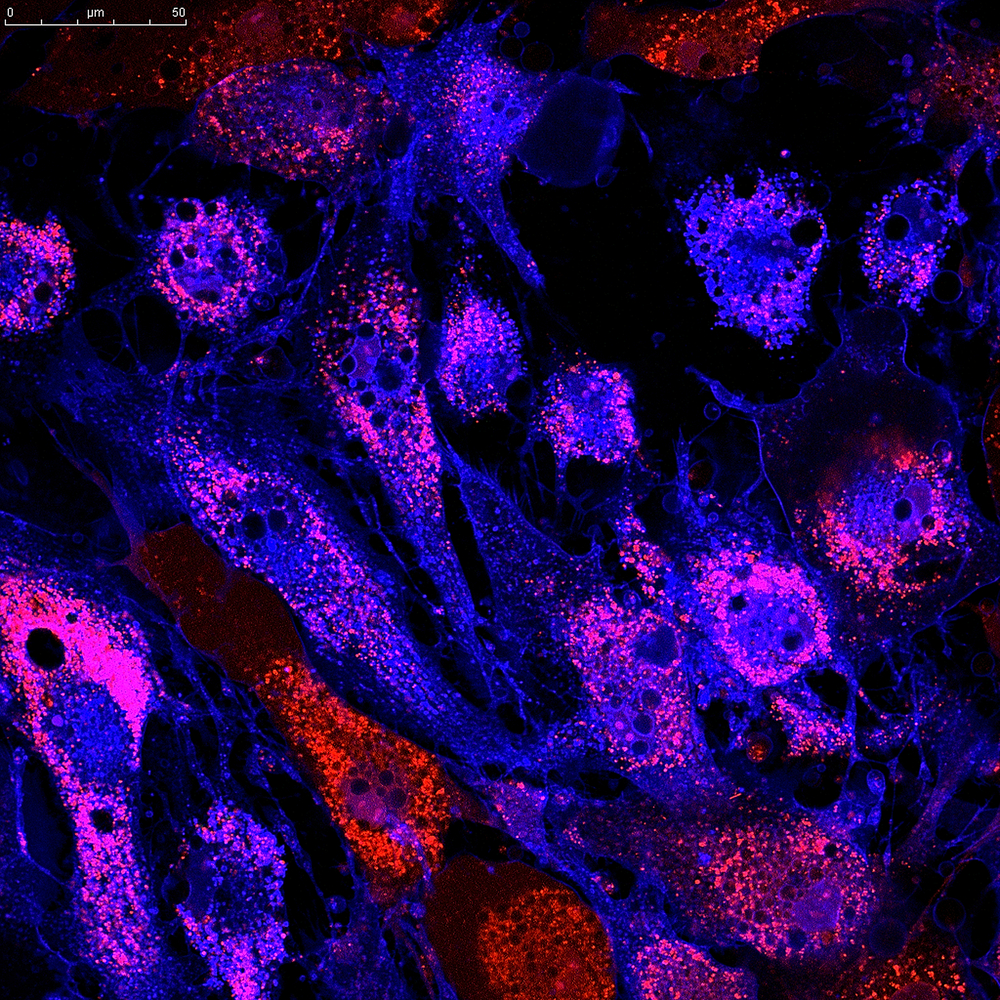

Moreover, CDH11 was present on both macrophages (detected by a protein called CD68) and myofibroblasts (detected by another marker, called alpha-SMA). In normal non-fibrotic lung tissue, CDH11 was absent.

The team then used the bleomycin mouse model, an established model to study pulmonary fibrosis, to understand how CD68-positive macrophages were associated with the abundance of alpha-SMA-positive myofibroblasts.

They found that, seven days after the induction of fibrosis by bleomycin, macrophages accumulated in the lungs, which correlated with a higher level of CDH11 production as well as alpha-SMA abundance.

Researchers then took cells from these mice, cultured them in the lab, and saw that the space between macrophages and lung fibroblasts was enriched with CDH11, forming junctions or “molecular hugs” between the two cell types.

“We liken it to a handshake,” Boris Hinz, PhD, the study’s lead author and a distinguished professor in the Faculty of Dentistry, said in a press release.

A special type of “profibrotic” macrophages, called M2 macrophages, were found to be the ones actually promoting the transition from fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, a process that was dependent on TGF-beta 1.

Further experiments confirmed that TGF-beta signaling in myofibroblasts occurred only when the cells were at a proximity of 100 micrometers (o.1 millimeters) or less from M2 macrophages, showing why the CDH11-mediated “hug” is the underlying mechanism promoting the cell’s profibrotic profile.

When discussing the link between uncontrolled fibrosis and the CDH11-mediated hug, Hinz noted that “the big question is: Why does it get out of control? We can’t really say why it doesn’t turn off, but this might be a reason.”

These findings suggest that “interfering with CDH11 accumulation or function, or both, in inflamed and fibrotic tissues would target inflammatory signaling and enable separation of both cell types to eventually terminate profibrotic communication,” the researchers wrote.