Anticoagulant DOACs Better Than Warfarin in IPF, Analysis Finds

Use of the well-known anticoagulant therapy warfarin in people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is associated with reduced transplant-free survival, but direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are not, a study found.

While more studies comparing warfarin to DOACs are warranted, the authors recommended using DOACs rather than warfarin until more direct evidence is available.

The analysis was published in the journal Chest, in the study, “Association Between Anticoagulation and Survival in Interstitial Lung Disease: An Analysis of the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (PFF) Registry.”

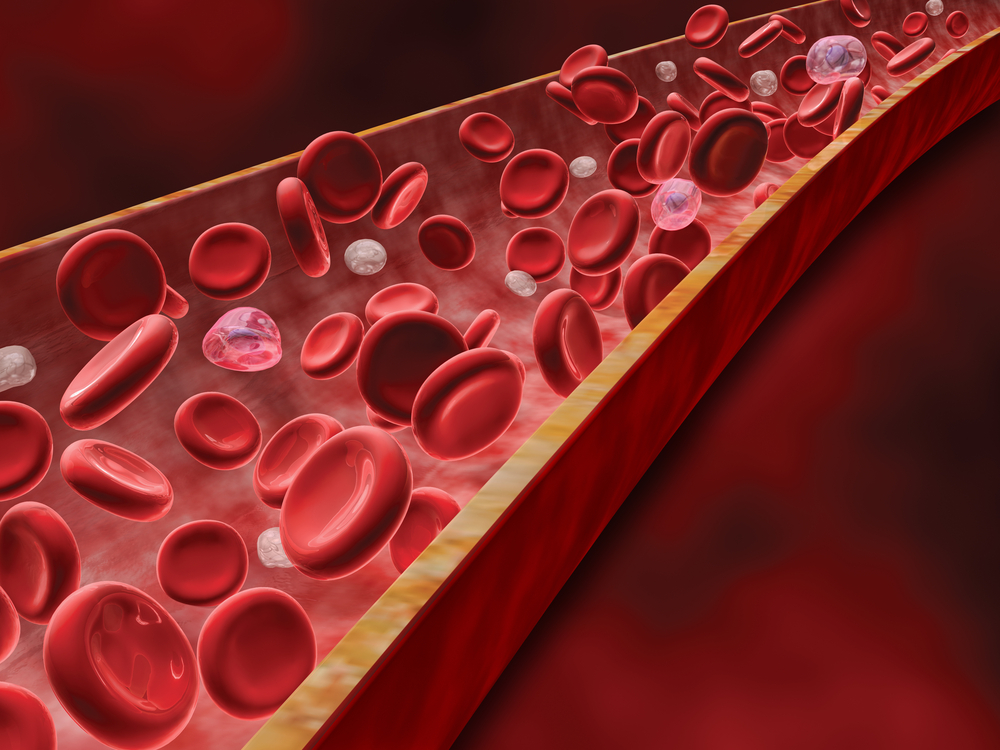

Abnormalities in blood clotting (coagulation) are thought to play a role in the development of IPF because some proteins involved in the clotting process stimulate fibrosis. Moreover, studies have shown a higher prevalence of coagulation-related medical conditions in people with IPF than in healthy individuals.

These findings suggest that anticoagulant medications may be a potential therapeutic approach in IPF. However, while early studies supported this approach, a randomized control trial testing the well-known anticoagulant warfarin as a treatment for IPF was terminated early due to increased mortality risk in those treated with the medication.

It was proposed that the differences in these studies were due mainly to the type of anticoagulant used.

Warfarin is an effective anticoagulant that works by blocking the vitamin K-dependent production of blood-clotting factors. It is thought that it also interferes with protein C, which prevents blood clotting and could lead to the release of inflammatory proteins, potentially worsening IPF outcomes.

DOACs are an alternative class of anticoagulants that suppress clotting by directly blocking the action of blood-clotting proteins such as thrombin and factor Xa. Pre-clinical studies have shown DOACs are able to reduce fibrosis in IPF mouse models.

To investigate the potential of other anticoagulants as IPF treatments, a team led by researchers based at Inova Fairfax Hospital in Virginia collected patient data from the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (PFF) Patient Registry (PFF-PR), which contains clinical information for a mixed population of more than 2,000 patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) — a group of disorders characterized by progressive scarring of lung tissue, including IPF.

“We performed an analysis of the PFF-PR to characterize the prevalence and type of anticoagulant agents prescribed for patients with ILD, as well as the association of anticoagulant use with survival in ILD, specifically IPF,” the researchers wrote.

There were 1,911 ILD patients selected for the analysis, including: 1,176 (61.5%) IPF subjects; 201 (10.5%) with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) other than IPF; 287 (15.0%) with connective tissue disease-associated ILD; 152 (8.0%) with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; and 95 (5.0%) had “other” ILDs.

Of these, 174 (9.1%) patients were treated with anticoagulants, with 93 (4.9%) prescribed a DOAC and 81 (4.2%) warfarin. Of the 93 patients taking DOACs, 84 received anti-factor Xa medications, which included 49 IPF patients. Nine participants were given anti-thrombin therapies, of which eight were IPF patients.

Data showed that among the IPF patients in the group analyzed, there were 80 deaths (6.8%), 36 transplants (3.1%), and 20 withdrawals (1.7%).

Overall, the analysis found that in ILD patients who received anticoagulants, the transplant-free survival was significantly reduced compared to those who did not receive the medications.

After adjusting for various factors — including sex, heart health, cancer, obstructive lung disease, diabetes, and pulmonary hypertension — the use of anticoagulants was suggestive of an association with mortality, but no longer was statistically significant.

When analyzed by type of anticoagulant, data showed a twofold increased risk of mortality or transplant in patients receiving DOACs, while there was a more than two-and-a-half times greater mortality/transplant risk for those receiving warfarin.

Importantly, after adjusting for various factors, only warfarin, and not DOACs, were associated with reduced survival.

A subgroup assessment of the IPF patients alone showed similar results, with estimates demonstrating an association between anticoagulation therapies and reduced transplant-free survival.

In IPF patients, a hazard analysis found only warfarin (but not DOACs) associated with a significant increase in death or transplant risk. This relationship with warfarin was maintained after adjustment for age, sex, lung function, walking tests, and co-existing conditions.

In contrast, increased risk of death or transplant was not found in IPF patients given DOACs after adjustments.

Overall, “the need for anticoagulation is associated with an increased risk for death or transplant in patients with ILD, in both the IPF and non-IPF population,” the researchers wrote. “Anticoagulation with warfarin specifically appears to be associated with reduced transplant-free survival.”

“Further study comparing use of DOACs to warfarin in patients with ILD is warranted,” the team added.

The researchers recommended that until more evidence is available, “it may be prudent to utilize DOACs preferentially over warfarin.”