Why I’ve Used Multiple Models to Track My IPF Progression

When I learned that the prognosis for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) patients is about five years after diagnosis, I started wondering how my disease would progress. I didn’t think my progression would follow the usual, defined stages. I believed I would have an acute exacerbation and go directly from diagnosis to death.

Traditional staging is determined by a patient’s forced vital capacity (FVC) test score. The test involves using a spirometry device to measure maximal expiration and inspiration. I read about the various stages of IPF but didn’t put much stock into any of them. In my support group, we didn’t talk in terms of stages. None of my pulmonologists discussed the stage models with me.

My presumption about exacerbations came from watching my friends with IPF. Their health would worsen during the cold Midwestern winters in the U.S. until they had an exacerbation and were hospitalized for two or three weeks. This setback would place them in stage 4. Given the severity, a lung transplant was unlikely. They passed away within a year.

Pre-transplant analysis

It became evident that my initial concept of my IPF progression was wrong. As my disease developed, it didn’t follow the defined stages, but instead appeared like a combination of several. My progression best fits the stages defined by National Jewish Health (NJH), which focuses on oxygen needs, with my FVC scores playing a supporting role.

My progression was slow thanks to the treatment Esbriet (pirfenidone), and I remained stable from my diagnosis in 2014 until December 2019.

In January 2020, I started to have more shortness-of-breath episodes. They were mild but concerning. I wanted to find a cause, so I looked at any changes. My diabetes treatment had changed to insulin. I scrutinized this event, but couldn’t connect it to my shortness of breath. I desperately wanted to find the cause because I didn’t want my lungs to worsen.

My need for oxygen continued to increase. By May, my FVC score had decreased by more than 10%. It was time to move up my annual lung transplant evaluation, which led to my transplant.

Post-transplant analysis

To better understand my progression, let’s look at it from a post-transplant perspective using various models:

- IPF doesn’t have stages, because each person’s progression is unique

- NJH model (IPF stages are based on oxygen needs)

- Traditional model (IPF stages are based on FVC test scores)

- GAP risk assessment system (IPF prognosis is estimated based on gender, age, and physiology)

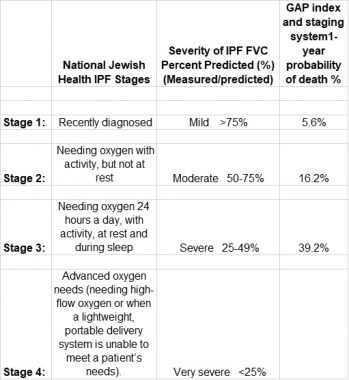

The following table compares staging models:

A comparison of IPF staging models. (Courtesy of Kevin Olson)

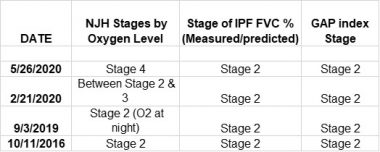

Following is a four-year summary of my lung decline defined by each model. I was stable from October 2016 until February 2020, when all models indicated I was in stage 2. As my need for oxygen increased, the NJH model placed me in stage 4, whereas the FVC and GAP models had me in stage 2.

Kevin’s IPF progression, according to various staging models. (Courtesy of Kevin Olson)

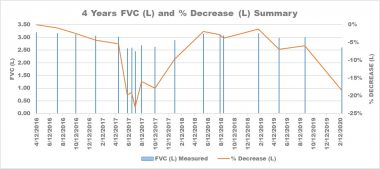

Early on, my interstitial lung disease pulmonologist said that a 10% decline in FVC scores meant it was time for a transplant evaluation. Usually, this drop is evaluated over a period of six to 12 months. For analysis, I charted my FVC measurements and the percentage they changed over four years.

Kevin’s FVC measurements and percentage decrease over four years. (Courtesy of Kevin Olson)

From April 2016 to April 2017, my decline was slow. Then, I had a significant drop in May. That month, I went into atrial fibrillation. My decline triggered the transplant evaluation process.

In August 2017, I had my first transplant evaluation. By then, my condition had improved enough that I was no longer ready for a transplant. It took a year to return to my 2016 FVC levels. In February 2020, my FVC levels started to decrease substantially again. My annual transplant evaluation was moved up, and I had my transplant in August 2020.

To properly analyze my IPF progression, I must look at all models and figures. For example, when I was declining, I considered the percentage drop in my FVC levels rather than my stage.

Another tool we can use is the du Bois Score for IPF Mortality. It calculates a patient’s need for a transplant by determining their one-year prognosis using pulmonary function test and clinical indicators. My one-year mortality risk was 40-50%.

Because IPF progression is unique to each patient, we can’t depend on a single method. Doing so could give us a false impression. Instead, we must define our own progression. Talk with your pulmonologist to determine the best methods for tracking your IPF.

***

Note: Pulmonary Fibrosis News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Pulmonary Fibrosis News or its parent company, Bionews, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to pulmonary fibrosis.

Richard Martin

Thank you Kevin for your detailed progress of IPF. I appreciate the charts you provided especially the staging models.

I found them helpful and useful. I am not a transplant candidate but have had IPF since 1/2018. Your report encourages me to have a detailed discussion with my pulmonologist about best tracking methods.

Kevin Olson

Hi Richard.

You are welcome, and glad you found my column helpful. Each IPF progression is hard to understand, and your discussion with your pulmonologist will be beneficial.

Kevin

Marilyn Cellucci

Dear Kevlin,

Great analytical article! As the scientific type, I enjoyed the article.

In the year of 2016, you were fairly stable. This has always puzzled me and no one seems to have the answer to the question. Why do so many of us remain stable for a length of time and then go downhill? I am sure there are researchers working on the reason. If it could be found, what a breakthrough it would be!

I was diagnosed in 2010 and had been stable until 2018 when I developed more scarring but not a lot of breathing problems. From 2018 to the present, I have had a lot more scarring, but relatively minor breathing problems. I consider myself very lucky so far. I am going to speak with my pulmonologist as to when I should start Pulmonary rehab.

Thanks for your narrative.

Kindly,

Marilyn

Kevin Olson

Good day, Marilyn.

Thank you for reading my column. I am happy to hear you enjoyed it. How long a person remains stable is a good question but a hard one to answer. Glad you have been stable for years. That is an excellent idea for checking on starting Pulmonary Rehab. I wish you the best of luck in the future.

Kevin

Earl Robinson

Kevin, good article.

I've been diagnosed with IPF in 2017 with a cough being what cause me to go to the pulmonologist. I started with OFEV 150 mg twice a day but due to liver issues the was reduced to 100 mg 2X/day. I continue to take OFEV and was diagnosed with PAH (pulmonary arterial hypertension) about a year ago. Early this year I started on a new drug, TYVASO, now I'm up to 21 breaths, 4X/day using a nebulizer which takes the medication directly to the lungs and related arteries to the heart. So far I'm fairly stable on 6 liters at night and rest and 10 liters of O2 with active. I'm having difficulty finding a POC (portable oxygen concentrator) and am now using O2 tanks until I can find a POC that will deliver the O2 I need.

I've had this idea of a Blue Tooth or wireless controller so I can adjust the levels of O2 being delivered by the stationary concentrator I have in the house so I can change the # of liters of O2 to match my activity levels. So far I have struck out. During the day when I'm sitting I don't need 10 L of O2 but when I want to move around I can't get to the concentrator to change the setting and I don't want to put my wife to doing anymore that she already has to do for me. I'm sure there are others that could use this wireless controller if it were available. This spells OPPORTUNITY for some young techy.

All the best to all of you IPFer's, Earl

Kevin Olson

Earl. I appreciate your interest in my column. I enjoyed your story. I fully understand your situation with the home oxygen concentrators and liter setting. I have seen others talk about blue tooth oxygen regulators but not real progress.

Kevin Olson