When Pictures Really Are Worth 1,000 Words

X-rays highlight the miracle of columnist Sam Kirton's bilateral lung transplant

During my pulmonary fibrosis journey, I learned that one of the best things I could do for myself was to become an active voice on my care team.

As a patient diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) more than five years ago, I wanted to know more about this disease that was taking my life. My goal was not to become my own doctor, but to better understand what my care team was telling me and to be able to express my views. My care team was excellent about asking for my input when making decisions about my care.

Because of this collaborative relationship, one day, when members of my care team were looking at an X-ray of my lungs, I decided to look at it with them. Over time, these X-rays began to tell an important story.

Light and dark

Pulmonary fibrosis is primarily a disease of the lungs. But as the fibrosis, or scarring, progresses, it becomes more difficult for oxygen to reach other parts of the body, including other organs and the brain.

From my diagnosis in January 2017 to my bilateral lung transplant in July 2021, I watched my lungs change in each new X-ray image. A lung full of air is black in an X-ray image. That was not what I witnessed from the first X-ray I saw. During those four and a half years, I watched the IPF progress as my lung capacity decreased. The air just had nowhere to go.

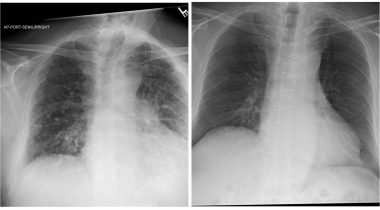

From left, an X-ray image of Samuel’s lungs on July 9, the day before he had bilateral lung transplant; an image of his new donor lungs. (Courtesy of Sam Kirton)

Oxygen saturation

As my IPF progressed, it affected my oxygen saturation levels. Oxygen saturation is expressed as a percentage of oxygen that is able to bind with hemoglobin in the bloodstream. In a healthy adult, that number is 95% or higher. This is typically measured with a pulse oximeter or a finger clip at a clinic.

I have carried a pulse oximeter with me for more than five years. During the first four years, I watched my oxygen saturation levels decline over time. From my diagnosis until late 2019, I did not require supplemental oxygen, although my oxygen saturation levels would drop to the low 90s. During the summer of 2019, it became more common to see my saturation levels drop below 90%. As fall approached that year, my oxygen saturation levels dropped below 87%.

At that level, the brain and other organs don’t receive the oxygen they need to perform effectively. In November 2019, the time had come for me to use supplemental oxygen. My saturation levels would dip to the upper 70s during exertion, and supplemental oxygen would be increased. Oxygen was required 24 hours a day, and I was using 7 liters per minute to walk across the room. My lungs could no longer deliver the oxygen levels I needed.

It was time for a change

I was originally approved for lung transplant in March 2020, but I deferred because COVID-19 was just beginning to spread at an alarming rate. In consultation with my care team, we determined that it was best for me to continue with my native lungs for the time being. Almost a year later to the day, I was listed for transplant.

In the above photo, the X-ray of the lungs on the left was taken on July 9, when I was admitted to Inova Fairfax Hospital in Virginia, for a bilateral lung transplant. The areas that normally would be filled with oxygen had shrunk considerably.

I went into surgery July 10, and after approximately nine hours, I was taken to the cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) shortly after noon on the same day. I would remain sedated and intubated until 5 p.m. July 11.

The gift of life

As the CVICU team brought me out of sedation and prepared to extubate me, my wife, Susan, leaned over and asked me if I was ready to take my first breath. I shook my head no. It was one of the scariest moments I had ever experienced.

But I did take that first breath.

The X-ray on the right shows the lungs that have given me a second chance at life. They are so full of air. If you look closely, you can see the wires that held my sternum together while it healed.

My donor, who is unknown to me, gifted me a beautiful set of lungs.

Transplantation is a very personal decision. My bilateral transplant was absolutely the right decision for me. Looking at the picture on the left is a somber reminder of where I was on my journey just last year. The picture on the right is my future, a life in which the best is yet to come.

I keep a picture of the lungs on the right on my phone. I also carry a pulse oximeter, and on occasion, I measure my oxygen saturation level to marvel at a reading of 99%-100%. Those lungs are the reason I intend to make every breath count.

Note: Pulmonary Fibrosis News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Pulmonary Fibrosis News or its parent company, Bionews, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to pulmonary fibrosis.

John Gould

Sam a question for you, I am 69 and O blood type, have 24% good oxygen producing lungs left, both lungs are diseased just about the same percentage, my recent lung xrays look like your pre transplant xrays, I use 6 litters per minute but off O2 even though my blood O2 goes down from the mid 90s to the mid to upper 80s as soon as I walk - I can walk around in the mid 80s, I begin coughing in the mid 80s, get a head ache in the mid 70s when I exert myself and get out of breath from the mid 70s down to low 60's - but as soon as I begin coughing I get on my O2 and once on 6 lpm my blood ox rises to 98 -100 within 15 seconds.

I don't need O2 to walk around, but if I want to walk around over 90s I do. I get a little bit dizzy when I reach the upper 60s low 70's.

I've read that you, and also talked to another post transplant guy, who both say right before transplant they couldn't walk 10 ft, with you saying you couldn't walk 10 ft on level 7.

My recent 6 min test said I should be on 8 without exertion and 14 with fast walking.

I am going on the waitlist next week. How close do my stats look to yours right before your transplant?

I know I'm a tough Vietnam vet and was a competitive athlete in tennis before PF so my body is used to pushing through stuff, so I'm probably doing more off oxygen in the high 70s and in the 80s then I should be doing - but that's how I'm built.

My 2nd question is that transplant committees push hard for recipients to agree to a single and double lung transplant, and push really hard if you are over 65. In my research, keeping A PF diseased lung subject to scarring progression and infection as well as only having 1 good lung which if it gets infected or rejected means its over for me - at my age it is unlikely a 2nd lung transplant would happen - so before I am listed next week I've taken a single lung transplant off the table and have consented to only a double lung transplant. At my transplant center looking at recent years transplants they were almost all double lung anyway. Your thoughts?

Lastly I've agreed to accept Hep C lungs (ie from a drug addict who overdosed) to increase my chances of getting lungs sooner, even though in addition to the anti rejection drugs I have go take, I'll have go take meds to cure the Hep C in me too. But in my research I've found Hep C lungs and non-Hep C lungs have the same longevity.

My research also found that only 25% of the remaining donor lung gets transplanted after the first is harvested for a single lung transplant, a stat that upsets me, so I figure if there is a 75% chance the remaining lung will be discarded - why shouldn't I get it if it is the best option for my health and longevity?

Thanks

John

Samuel Kirton

Hi John,

There are so many other variables but I can tell you that allowing your oxygen saturation to fall below 88% can be dangerous. If it does there is an increasing risk of damage to other organs. Damage to another organ may create a comorbidity that would change your transplant trajectory. Please talk to your care team about safe minimum oxygen saturation levels and what length of time is acceptable to revere to a reading at or above 90%.

Sam...