Study to Test If Wearable Device Can Predict Symptom Worsening

Written by |

crystal light/Shutterstock

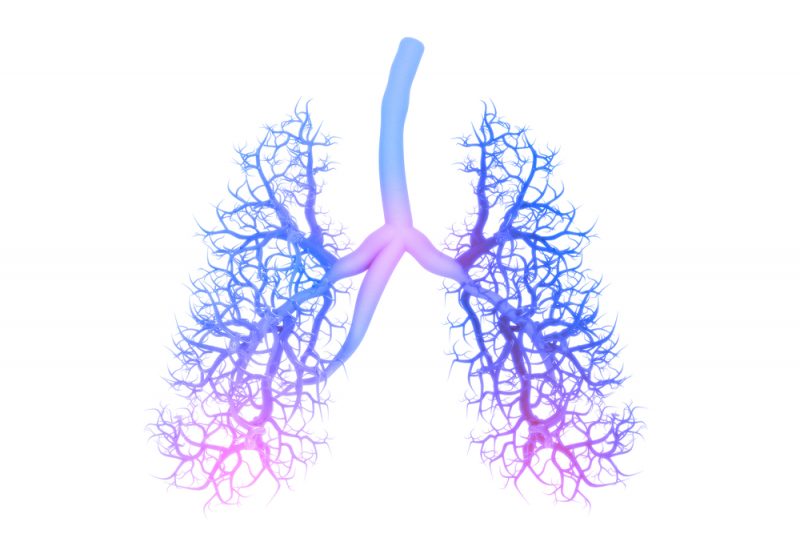

Researchers at the University of Alberta are studying whether combining a commercially available wearable device with artificial intelligence can effectively predict symptom worsening in people with chronic lung conditions, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Developed by New York-based Health Care Originals to monitor asthma, the ADAMM-RSM is a small, flexible, and comfortable patch-like device that can be attached to the side, front, or back of the upper torso under clothing.

ADAMM-RSM can monitor coughing, breathing patterns, presence of wheeze, heart rate, temperature, and activity level for at least eight hours per day, and transfers the data via Bluetooth to the user’s electronic device. The user can then review the collected info in a web portal and in a smartphone app.

The data are analyzed through unique algorithms to help define each user’s norm, so that whenever symptoms deviate from that norm, the device vibrates and sends text notifications to designated persons.

“This is important because we want to detect any variations as they occur, before the patient needs to go to the ER,” Giovanni Ferrara, MD, PhD, the leader of the pilot study, based in Edmonton, Canada, said in a press release.

The device is able to “track clinical signs and symptoms in an objective way, helping to inform treatment decisions tailored to patients’ needs, thus providing a more precise control of their disease,” added Ferrara, who is a professor of medicine and the director of the pulmonary medicine division of the university’s faculty of medicine and dentistry.

ADAMM-RSM has the potential to monitor the health condition of patients remotely and to detect or predict symptom worsening in a more consistent and proactive manner.

The pilot study, divided in three phases, will evaluate whether ADAMM-RSM and its algorithms can be tailored to monitor respiratory conditions other than asthma, such as IPF, cystic fibrosis, recent lung transplants, and tuberculosis.

It will explore “the possibility to predict when it’s the right time to see your physician based on the data collected by the device and artificial intelligence algorithms, before you get in trouble,” Ferrara said.

“That’s what we really want to see in health care today. We don’t want a different way to look at the same thing — we want new tools,” he added.

Should the initial feasibility study, which is planning to enroll 40 people with chronic lung diseases, prove successful, researchers will run the second and third phases in specific patient populations and in a greater number of patients.

Additional research also seeks to analyze and develop algorithms that can help predict major respiratory events, such as hospital admissions or ER visits.

“If everything works, [the study] could easily be done within two to three years,” Ferrara said.

The physician believes that the project was only possible due to Edmonton’s “unique circumstances,” where there is a combination of clinical and technological expertise — including in artificial intelligence — that promotes the development of new medical devices.

Jared Dwarika, Health Care Originals’ co-founder, said that “the beauty of the technology is that Dr. Ferrara is looking at a lot of conditions using the same platform,” and that the study may in the future include conditions that “he might not be considering now.”

“This is the future of healthcare,” Dwarika said, adding that “feedback on your treatment is going to be tailored to you, rather than using a generic set of parameters.”

The fact that the device can be worn discretely under clothes is also considered a plus.

“A common problem with these types of devices is that you don’t want to advertise that you’re monitoring a medical condition — you don’t have to broadcast it,” said Sharon Samjitsingh, Health Care Originals’ co-founder.

In addition to Ferrara and Health Care Originals, the study is being supported by other experts at the university, the Northern Alberta Clinical Trials and Research Centre, ST-Innovations, and the university’s Precision Health Innovation, Research and Technology Ecosystem signature area.